Delhi Woman Demands Justice After Losing Husband and Three Sisters in Deadly Goa Nightclub Fire

Pakistan Revives Sanskrit Studies After Decades, LUMS Plans Courses on the Gita and Mahabharata

Lahore, December 13:

In a move that is being seen as both symbolic and academic, Pakistan has reintroduced Sanskrit into its classrooms for the first time since the Partition of 1947. The initiative has been launched at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), where a four-credit course on the classical language is now being offered, marking a significant step toward reconnecting with South Asia’s shared intellectual and cultural past.

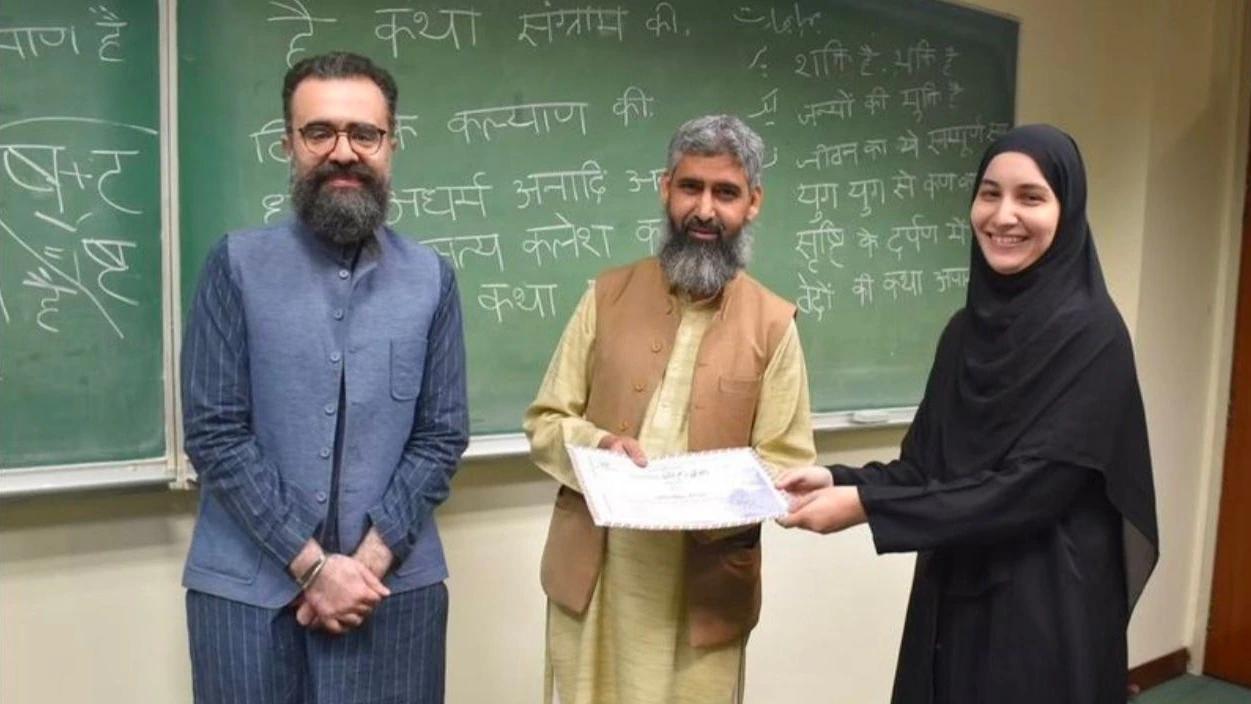

The course grew out of a three-month weekend workshop that attracted strong interest from students, researchers and scholars. Encouraged by the response, the university decided to formalise the effort and include Sanskrit as part of its academic offerings. Alongside learning the language, students are also being introduced to cultural texts linked to it, including an Urdu rendition of “Hai katha sangram ki,” the well-known theme from the Mahabharat television series, to help them connect with the broader narrative tradition.

Dr Ali Usman Qasmi, Director of the Gurmani Centre at LUMS, said the revival of Sanskrit studies is long overdue. He pointed out that Pakistan holds one of the richest but most overlooked collections of Sanskrit material in the region. The Punjab University library, he noted, houses a large number of Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts that were carefully catalogued in the 1930s by scholar JCR Woolner. However, since 1947, these texts have largely remained untouched by local academics and have mostly been accessed by foreign researchers.

According to Dr Qasmi, training scholars within Pakistan will change this reality. He said the university hopes to build local expertise so that Pakistani researchers can study, interpret and preserve these manuscripts themselves. Looking ahead, LUMS also plans to introduce dedicated courses on the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad Gita. “In the next 10 to 15 years, we could see scholars based in Pakistan who specialise in the Gita and the Mahabharata,” he said, describing it as a realistic and meaningful goal.

Another key figure behind this initiative is Dr Shahid Rasheed, Associate Professor of Sociology at Forman Christian College, whose efforts played a major role in bringing Sanskrit back into academic discussion. Dr Rasheed shared that his own journey with classical languages began with Arabic and Persian before he turned to Sanskrit. He learned the language largely through online platforms, studying under well-known international scholars, including Cambridge-based Sanskrit expert Antonia Ruppel and Australian Indologist McComas Taylor.

Dr Rasheed said it took him nearly a year to work through classical Sanskrit grammar and that his learning process is still ongoing. He acknowledged that many people question his choice to study Sanskrit, but he firmly believes the language belongs to the entire region. He explained that Sanskrit has deep historical roots in South Asia, noting that the famed grammarian Panini came from this region and that significant literary and intellectual work connected to Sanskrit was produced here over centuries.

Describing Sanskrit as a cultural monument, Dr Rasheed said it should not be seen as belonging to any one religion. “It is ours too,” he said, stressing that languages carry shared wisdom and history rather than religious boundaries. He believes that reclaiming Sanskrit as part of Pakistan’s intellectual heritage can help broaden academic thinking and cultural understanding.

Dr Rasheed also spoke about the wider impact such initiatives could have on South Asia. He suggested that the region would benefit if people showed greater interest in each other’s classical traditions. He imagined a future where more Hindus and Sikhs in India study Arabic, while more Muslims in Pakistan learn Sanskrit, creating space for dialogue rather than division.

The revival of Sanskrit studies at LUMS has sparked discussion across academic and cultural circles, with many viewing it as a hopeful sign of openness and curiosity. While the programme is still in its early stages, it reflects a growing willingness to engage with the past in a thoughtful and inclusive way. For Pakistan, the return of Sanskrit to the classroom is not just about language learning, but about rediscovering a shared heritage and building bridges through knowledge rather than walls.

Pakistan Revives Sanskrit Studies After Decades, LUMS Plans Courses on the Gita and Mahabharata

For the first time since 1947, Sanskrit has returned to classrooms in Pakistan, marking a quiet but powerful shift in how the country is engaging with its shared cultural past. The Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) has launched a four-credit Sanskrit course, opening doors to a language that once shaped much of South Asia’s intellectual and literary life.

The course grew out of a three-month weekend workshop that saw strong interest from students and scholars. Encouraged by the response, the university decided to make it part of its formal curriculum. Students are not only learning the basics of the language but are also being introduced to cultural texts connected to it, including an Urdu version of the iconic Mahabharat theme, helping them understand the stories and ideas behind the words.

Dr Ali Usman Qasmi of the Gurmani Centre at LUMS said Pakistan holds a rich but largely ignored Sanskrit archive. The Punjab University library houses rare palm-leaf manuscripts that were catalogued in the 1930s but have barely been studied locally since Partition. Training scholars within Pakistan, he said, will help change that. The university also plans to introduce future courses on the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad Gita, with hopes of producing Pakistan-based scholars of these texts in the next decade.

The effort has been strongly supported by Dr Shahid Rasheed of Forman Christian College, who studied Sanskrit after learning Arabic and Persian. He believes Sanskrit belongs to the entire region and should not be tied to any one religion. Calling it a cultural monument, he says learning each other’s classical languages can help South Asia move toward understanding instead of division.

In a region often shaped by borders, this move reminds us that knowledge still travels freely.

Add Comment